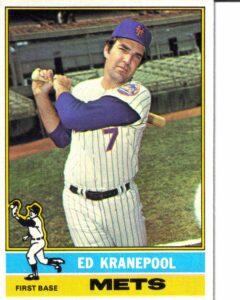

I was a big fan of Ed Kranepool’s. He was a classy Met on the bad teams I knew growing up. He was a great pinch hitter, racking up a .486 average by going 17 for 35 in 1974, which was a disappointing year overall for a team that had been to the World Series the previous year. (He hit .286 in two NLCS but had just one hit in two World Series—that hit was a home run in Game 3 in ’69.)

Ed wasn’t about the stats, but he played so long he ended up being about the stats. When Cleon Jones played his final game as a Met in 1975, he held many of the all-time Mets offensive marks. By the time Krane left the game in 1979—wearing the home uniform in all 18 seasons as a Met and still just 34—he owned just about every record and held most of them until David Wright came along. Steady Eddie’s 1,853 games are still 268 more than Wright. Those pinch hitting appearances really add up.

Krane debuted as a 17-year-old in 1962, a local kid who grew up a Yankees fan but he signed for big money from the Mets. He used future teammate Tommie Agee as a yardstick; Agee had gotten $60,000 to sign with Cleveland and so Eddie, who’d just graduated from James Monroe High School in the Bronx, told the Mets he thought $80,000 was fair. The Mets, who were already losing plenty, didn’t want to lose the local kid to the White Sox, so they signed him. Ed had never really wanted to leave New York—and he never did.

Because the Mets were so bad, much was expected of him. One thing that comes through in his entertaining bio, The Last Miracle (with Gary Kaschak), is that he didn’t love his managers. Yet he was very fond of Casey Stengel, who could be tough on kids. Ed was never shy about wanting to play more, and he batted .300, .323, and .292 from 1974-76. When the Mets went into the tank in 1977, the team decided to give the younger players a chance. It might have been a good plan—if the younger players had been good.

Ed hit 118 home runs in his career, but the one he hit to win game two of the 1978 season sent me into a frenzy of delight and fury. I was thrilled by the game-winning shot against Montreal, but furious that my dad made us go home from the game early with the Mets down several runs because our hands were turning white on the frigid April afternoon. Steady Eddie’s walkoff blast made me resolve for years to never leave a game early—until I had kids and I understood Dad’s concerns a little better.

Ed never knew his father, who was killed in Europe during World War II when his mother was pregnant with him. In his book he noted that because of this he was exempt from military service, which many of his Mets teammates dealt with during the 1960s and 1970s. Ed had to deal with growing up without a father.

He always had an edge when he gave interviews. Ed didn’t dole out pat answers; he said what he felt. He was the one Met I talked to about the 1973 postseason pitching rotation who threw Yogi Berra under the bus. Someone had to say it. Krane survived Yogi at Shea, along with Casey, Wes Westrum, Gil Hodges, and Joe Frazier, plus interim managers Salty Parker and Roy McMillan. He did not survive Joe Torre, a veteran infielder whom he’d platooned with at first base and considered a friend until he took over as manager. Krane actually put together a group to buy the Mets months after his last at bat with the team—hit 1,418 was a pinch-double as the moribund ’79 squad barely avoided 100 losses. Owning the team didn’t work out for Kranepool—he already owned the record book—but having been a Met for so long he knew about long odds.

The odds were even longer when he needed a kidney transplant in his 70s. He got the organ transplant amid great huzzahs from the Mets community. He sold memorabilia to help pay for medical care. I went to his home on Long Island, thanks to his agent Marty Gover, who’d bought some of my books for some promotion. In turn, I bought some photos from the Kranepool collection that he allowed me to use in a book on Shea Stadium. I bought a picture from Krane but never thought to ask to get a picture with him.

I did see him on the field at Citi Field before a game 10 years ago. I was promoting Swinging ’73 and he’d given me that great interview. I had a copy of it and—unlike many times when you get a “send it my agent” or something—Ed took the book in his hand and looked it over. The time on the field non-uniformed personnel was drawing nigh and I figured we were done, but we weren’t. He held up the book and called out, “Hey, thanks!” That’s what it’s taken me so many words here to say to him. Krane, you will be missed.